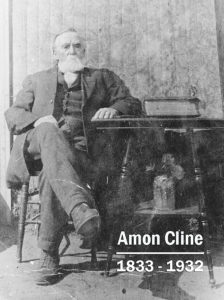

Amon’s life story began pretty much as anyone else’s did in 1833. However his journey though life would be long, difficult, painful and at times extremely dramatic. He lived to be nearly 99 years old and survived experiences most would never want, nor ever be able to endure. Amon Cline had the mind set of never giving-up. The good, bad, terrible pain and tragic losses in the 1800’s were surely blended with great health and a wonderful loving and caring family.

Amon Cline was born in Burke County, North Carolina, on October 1, 1833. His parents were Michael S. and Rachael S. Cline. Amon was not quite 3 years old when in San Antonio, Texas, James Bowie, Colonel William Travis, Davy Crockett and nearly 180 more lost their lives defending the Alamo.

Cherokee County, Georgia, was Amon’s home when on January 18, 1855, he married 17 year old Sarah Ann Frances Manders, Cline was 22. The couple had six children; Elizabeth, born before the Civil War (March 17, 1858) and named after his older sister, then James, Nancy, Buena, Susan and Benjamin.

On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States, defeating democratic front-runner, John C. Breckinridge. Abraham Lincoln who took office on May 4, 1861, was America’s first republican president. A few weeks prior to Lincoln taking office, hostilities between the northern and southern United States began on April 12, 1861, and with it the beginning of the Civil War.

It was Tuesday, March 4, 1862, when Amon Cline enlisted in the Confederate Army to fight in the war. Many believed it would be a short-lived conflict, lasting no more than 90 days. But instead the battles continued for four long and bloody years.

The American Civil War raged from 1861 to 1865

The 28 year old Cline was a private in Company A, 43rd, Georgia Infantry. Infantry is the general branch of an army that engages in military combat on foot. As the troops who engage with the enemy in close-ranged combat, infantry units bear the largest brunt of warfare and typically suffer the greatest number of casualties during a military campaign. The 43rd was a infantry regiment, first organized in April of 1862. In the Confederate Army—which was organized very much like the Union—a typical infantry regiment included about 1,000 men. The men of Amon’s 43rd Georgia Infantry were recruited from Banks, Cherokee, Forsyth, Hall, Jackson, and Pickens counties. At the time, Cline lived in Cherokee County. They were mustered into Confederate Service at Camp McDonald near Big Shanty, Georgia, between March 10, and April 10, 1862. “A” Company, the Cherokee Van Guards, was first formed in Cherokee County, Georgia. The commanding officers during the war were Colonel James A. Skidmore Harris, often called “Skid” and Colonel Hiram P. Bell. The regiment served in the brigade of Captain Seth M. Barton and Brigadier General Marcellus A. Stovall, all of these officers but Colonel James Harris survived the war. Despite their losses, it was later reported the regiment served with great distinction.

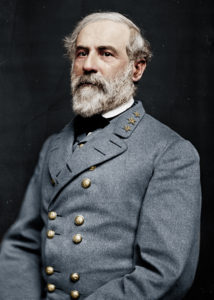

Amon fought bravely for two years behind the wise Confederate leadership of General Robert E. Lee. For the Rebel’s the Civil War was a loosing proposition, Lee’s Army was outnumbered by a vast margin of at least two-to-one. The 43rd Georgia Infantry’s first action was The Battle of Champion Hill, on May 16, 1862. It was a baptism by fire for the newly formed southern infantry.

Champion Hill was a bloody and decisive Union victory. Union General Ulysses S. Grant later wrote; “While a battle is raging, one can see his enemy mowed down by the thousand, or the ten thousand, with great composure; but after the battle these scenes are distressing, and one is naturally disposed to alleviate the sufferings of an enemy as a friend.” The Union losses totaled some 2,500. The Confederates suffered about 3,800 casualties.

Above: General Robert E. Lee

Then, the 43rd Infantry rushed with the Rebel army to fight in The Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, also called the Battle of Walnut Hills, fought just after Christmas, between December 26 and 29, 1862. This time the Union casualties were far less, 208 killed, 1,005 wounded, and 563 captured or missing; Confederate casualties were also fewer, 63 killed, 134 wounded, 10 missing.

The Battle of Chancellorsville was a major battle of the Civil War. It was fought from April 30 to May 6, 1863, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, near the village of Chancellorsville. The campaign pitted Union Army Major General Joseph Hooker’s Army of the Potomac against an army less than half its size, General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Chancellorsville is known as Lee’s “perfect battle” because his risky decision to divide his army in the presence of a much larger enemy force resulted in a significant Confederate victory. The victory, a product of Lee’s audacity and Hooker’s timid decision-making, was tempered by heavy casualties, including that of Lieutenant General, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. As Jackson and his staff were returning to camp on May 2, they were mistaken for a Union cavalry force by the 18th North Carolina Infantry regiment who shouted, “Halt, who goes there?”, but fired before evaluating the reply. Frantic shouts by Jackson’s staff identifying the party were replied to by Major John D. Barry with the retort, “It’s a damned Yankee trick! Fire!” A second volley was fired in response; in all, Jackson was hit by three bullets, two in the left arm and one in the right hand. Several other men in his staff were killed. Darkness and confusion prevented Jackson from getting immediate care. He was dropped from his stretcher while being evacuated because of incoming artillery rounds. Because of his injuries, Jackson’s left arm was later amputated. Jackson was moved to a nearby plantation named “Fairfield.” The General was thought to be out of harm’s way; but unknown to the doctors, he already had classic symptoms of pneumonia. He subsequently died of pneumonia eight days later, on May 10, 1863, Jackson was 39. General Lee’s difficulty in replacing his lost men as well as his inability to prevent the Union withdrawal effectively have led to his great victory being regarded as a Pyrrhic one.

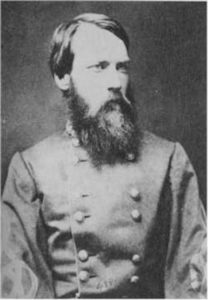

Two, valuable officers in Amon’s 43rd Infantry were lost during the next battle, the bloody Siege of Vicksburg, which unfolded between May 18 through July 4, 1863. Vicksburg was the last major Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. Colonel James A. Skidmore Harris was the first loss; he suffered a terrible gun shot wound to the leg, received while leading the 43rd at Baker’s Creek (Champion’s Hill), Mississippi, on May 16. The 34 year old sadly expired the next day. Brigadier General Seth Barton faired much better, he was captured by the Union Army on the final day, July 4th, when the Rebel’s were forced to surrender. Before his capture, General Barton reported the following on, June 18, 1863; “The heavy loss of the brigade (over 42 per cent) is the best evidence I can give of the good behavior of the men.”

Above: Brigadier General Seth Barton

Union casualties for the Siege of Vicksburg were 4,835; Confederate’s lost an unimaginable 32,697, another 29,495 men surrendered. General Barton was lucky, after his capture he was back in the war a year later, released in a prisoner exchange. Despite the long odds and overwhelming losses to his fellow Rebel forces, Amon had so far, managed to avoid capture and more importantly, survive without major injury.

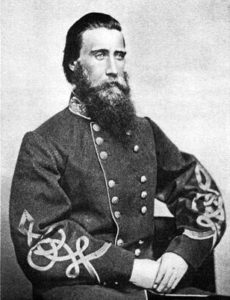

In mid-1864 the Union Army was advancing further and further south, the Confederate’s were losing the war. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was becoming increasingly frustrated with his front-line commander, General Joseph E. Johnston. Davis often criticized him for a lack of aggressiveness, and a much needed victory had eluded Johnston. The general’s strategy of maneuver and retreat was not popular with the Rebel high command.

Johnston had repeatedly retreated from Union General William Sherman’s superior forces. On July 17, Davis ordered Johnston relieved of his command and replaced by Lt. General John Hood. At 33, Hood was two years older than Amon Cline and temporarily promoted in rank to full general. The new Confederate general was the youngest man on either side to be given command of an army. Some thought the change of command from Johnston to Hood was extremely controversial. Replacing him with the brash Hood, practically on the eve of battle, has generally been regarded as a mistake. General Robert E. Lee gave an ambiguous reply to Davis’s request for his opinion about the promotion, calling John Hood “a bold fighter, very industrious on the battlefield…” but he could not say whether Hood possessed all of the qualities necessary to command an army in the field. It was a known fact, John Hood was actually fond of taking risks against his adversary, General Sherman.

Above: Lt. General John Hood

On July 20, 1864 the Confederate’s engaged the Union Army at the Battle of Peachtree Creek. Fought on the doorstep of Atlanta, Georgia, it was the first major attack by General John Hood. At Peachtree, the Union lines had bent but not broken under the weight of the Confederate attack, and by the end of the day the Rebels had failed to break through anywhere along the line. Estimated casualties were 4,250 in total: 1,750 on the Union side and at least 2,500 on the Confederate. General’s Hood and Sherman had survived.

Above: The Battle of Atlanta – July 22, 1864

On the morning of Friday, July 22, 1864, the Battle of Atlanta started just southeast of Atlanta, Georgia. The Union forces totaling 80,000 men were about to engage the smaller Confederate Army of 50,000. The Rebels fought 40,438 and took an aggregate loss of approximately 5,500. Fighting that day took place at the fringes of the battle at Decatur and at Beachtown, along the Chattahoochee River. The Confederates still held Atlanta proper, but the Federals ringed it with unrelenting force. Amon Cline was caught up in the one-sided blood bath, surely being an eyewitness to many of his close army friends killed in hand-to-hand combat, or simply shot dead. Confederate Major General William Henry Talbot Walker was among the Rebel losses. He was a career U.S. Army officer who fought with distinction during the Mexican-American War. Walker was severely wounded many times in combat, but on July 22, the 47 year old veteran was shot from his horse by a Federal picket, killing him instantly.

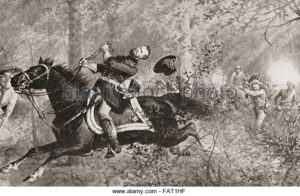

Union Major General James McPherson was also killed that fateful day. McPherson was riding his horse toward his Corps, when a line of Confederate’s suddenly appeared, yelling “Halt!” The surprised General abruptly wheeled his horse, attempting to escape when the Confederates opened fire and mortally wounded the officer. McPherson was one of the highest-ranking Union officers killed in action during the Civil War. Prior to the war, General McPherson and General Bell were West Point classmates. After hearing the tragic news of McPherson’s death, Bell wrote; “I will record the death of my classmate and boyhood friend, General James B. McPherson, the announcement of which caused me sincere sorrow. Since we had graduated in 1853, and had each been ordered off on duty in different directions, it has not been our fortune to meet. Neither the years nor the difference of sentiment that had led us to range ourselves on opposite sides in the war had lessened my friendship.” When General Sherman received word of McPherson’s death, he openly wept, then sat down and wrote a letter to McPherson’s fiancée Emily Hoffman. James and Emily had been engaged, the couple decided to postpone their wedding until the war was over. Emily never recovered from his death, living a quiet and lonely life until her death in 1891.

General Sherman eventually overwhelmed and defeated Hood’s Rebels. General Hood survived but lost a staggering 8,500 of his men. Sherman suffered 3,600 lost. Through all this carnage and bloodshed of July 22, private Amon Cline was among the lucky few who were captured alive. The battle continued as the city did not fall until September 2, 1864.

Above: Death of Union Major General James McPherson, July 22, 1864

As a Union POW, Amon was taken north to Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio. He of course was not alone, at least four other men from Amon’s 43rd Infantry were known to have been captured on July 22, 1864. Possibly caught along with Amon were private’s; Henry S. Goss, Green B. Sluder and David Weaver. Corporal Jacob H. Farmer was also in the group on July 22. Private William M. Childress was later nabbed by the Union Army on August 7. Then Second Corporal, Joseph H. Green fell into the enemy hands on August 13, like the others, captured at Atlanta. All of these men were sent to Camp Chase. Another man from the 43rd Infantry, private William A. Redding was apprehended near Atlanta, on July 22. Instead of being shipped to Camp Chase with the others, Redding was transported to Camp Douglas, Illinois, located just south of Chicago. He was released on April 6, 1865.

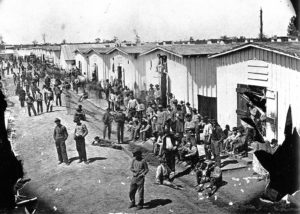

It is estimated 25,000 Confederate prisoners passed through its gates from 1861 to 1865. Camp Chase had a maximum capacity to hold 4,000 prisoners, but as the war years carried on, it soon held over 8,000 Confederates. The camp was an enclosed barracks prison. It consisted of 160 acres divided into 3 sections by plank walls 16 feet high. The prisoners were assigned to quarters in small houses or shanties measuring 16×20 feet. Each little shanty, with double or triple bunks arranged along the wall would hold 12 to 15 men. At one end of the shanty, a room was partitioned off as a kitchen with a small opening in the partition just large enough for a plate or cup to be passed through. The living quarters within the 3 camp sections were generally arranged in clusters of 6, with the buildings of each cluster about 5 feet apart. The clusters were separated by narrow streets or pathways. The streets, drains, and gutters of the camp were all in the same condition. The latrines were nothing more than open excavations. The stench that permeated the camp, mostly from the open latrines, was described as “horrible, nauseating, and disgusting.” The prison grounds were unlevel, soft clayish soil with poor drainage. Pools of water and deep mud would stand for several days after a mild rain. The roofs of the living quarters would always leak since they were not shingled. There were many prisoner complaints against the camp guards. Many of the complaints involved that prisoners were often shot by the guards when the prisoners misunderstood and stepped out of line during roll call, failed to quickly follow demands yelled down to them from the guards on the parapet, or gathered into large groups. Immediately to the south of the camp, and across a stream that ran along its edge, was a 10 acre site in which the dead prisoners were buried.

Two above photos: Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio

In mid-to late 1864, a smallpox epidemic hit the camp. Corporal Jacob H. Farmer was one of the men who became ill with smallpox. On September 21, Farmer died and was buried in the nearby Camp Chase Cemetery. Two weeks later on October 4, private Green B. Sluder passed away from smallpox. Sluder joined Farmer in the camp cemetery.

That year the prison population had expanded to a whopping 8,000 men. In November 1864, from various Union prison camps, there was an exchange of 10,000 sick and wounded prisoners between the North and South; Amon was not included in any of the exchanges. Before the end of hostilities, Union parolee guards were transferred to service in the Indian Wars, some sewage modifications were made, and prisoners were put to work improving barracks and facilities. Prison laborers also built larger, stronger fences for their own confinement, a questionable assignment under international law governing prisoners of war. Barracks rebuilt for 7,000 men soon overflowed, and crowding and health conditions were never resolved. In the camp’s unsanitary, crowded barracks prisoners also suffered from malnutrition and exposure during the harsh winters.

In December of 1864, two more men from Amon’s 43rd, also captured near Atlanta died in the prison camp. Private David Weaver passed away on December 21, he was infected with smallpox, then private William M. Childress expired from chronic diarrhea on December 23. Both were buried in the camp cemetery. Amon endured a cold, miserable and depressing Christmas of 1864 in these unimaginable living conditions.

Above: Today, the Camp Chase cemetery – 2,260 Confederate men are buried there

The last remaining prisoners were released from the camp in June and July 1865. As many as 10,000 prisoners were reputedly confined there by the time of the Confederate surrender. Amon Cline was among the more fortunate or lucky, now 31 years old, the battered, tired and half-starved Georgia war veteran took the required Oath of Allegiance and was finally released from captivity on Tuesday, May 16, 1865. Fellow 43rd private, 28 year old Henry S. Goss, also captured near Atlanta, on July 22, was set free one day ahead of Amon, on May 15, 1865. It wasn’t until June 11, that 22 year old Second Corporal, Joseph H. Green would be released from the POW camp. Of the brave men from the 43rd Georgia Infantry, Company “A” who were imprisoned at Camp Chase, only Amon Cline, Henry Goss and Joseph Green survived to be released. Between 1861 and 1865, only 37 men escaped from the camp, but 2,260 died there.

Back in December, 1863, Amon was included in the 43rd Georgia infantry which totaled 283 men and 251 arms. Less than a year later, in November of 1864, there were just 130 men still fit for duty. By that time, Amon was a prisoner of war. On April 26, 1865, the battle-weary unit survivors surrendered, the war was over. War losses for Amon’s home state of Georgia totaled 3,702 men. During the bloody Civil War, both sides suffered massive casualties with a combined totaling over 620,000 American lives lost. These casualties exceed the nation’s loss in all its other wars, from the Revolution through Vietnam. About a month after Amon was released from Camp Chase, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on Good Friday, April 14, 1865.

Above: “I’m a Good Ol’ Rebel” / performed by Hoyt Axton

By Major Innes Randolph, Jr., C.S.A. (1837-1887)

This Civil War poem was originally printed in 1914 in Collier’s Weekly.

Above: Amon’s 43rd Georgia Infantry (Civil War) Reunion, date unknown

When Amon Cline returned home from the Civil War in 1865, three long and terrible years had passed, the war and captivity was finally over. Now it was time for him to rebuild his life. Fortunately Amon’s loving wife Sarah and 7 year old daughter Elizabeth were eagerly waiting for him in Cherokee County, Georgia. Other’s returning home from the war had lost everything or much worse, had no one. Still, Sarah and young Elizabeth also had war time struggles in their past. Over the following years, five more children were added to the Cline family; James, Nancy, Buena, Susan and Benjamin.

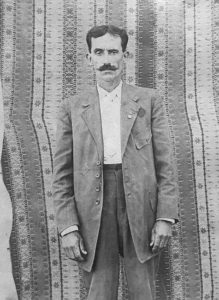

Above: Amon’s youngest child, Benjamin F. Cline, born October 22, 1874. Photo date unknown.

According to the 1870 Federal Census in Cherokee County, Georgia, Amon Cline was a farmer, his 32 year old wife, Sarah was illiterate, she could not read or write.

After the dawn of a new century (1900) the Cline’s left Georgia and moved west to the township of Wray, in Jefferson County, Oklahoma Territory, where Amon resumed his farming business. Tragedy struck the family in 1904, when Amon’s beloved 65 year old wife, Sarah Cline passed away on February 24th, the two had been married for 49 years. On her grave he loving wrote, “She was the sunshine of our home.”

Above: Grave site of Sarah Cline / “She was the sunshine of our home”

In May of 1906, Amon returned to Cherokee County, Georgia, where he and Sarah once lived. Back in Georgia, 73 year old Amon married 64 year old Rebecca Jane Pitman. The marriage took place on Thursday, May 31st. Rebecca or Beckie as Amon fondly called her, was never married and never had children, she would be Amon’s second wife. Once united, the elderly couple promptly returned to Amon’s home in southern Oklahoma. Later that year on November 16, 1907, Oklahoma was established as the 46th state in the Union. In 1915, Oklahoma’s Fifth Legislature approved the Confederate Soldiers’ Pension Bill. This Act provided for pensions for disabled and indigent Confederate soldiers, sailors, and their widows. On October 2, 1915, the day after Amon’s 82nd birthday he was granted a pension for his service in the Civil War.

Over his remaining lifetime, Amon lived in Wray and Grady, Oklahoma. Blessed with a long and fruitful life, Amon not only out-lived his first wife Sarah, but also Rebecca and most of his children. Amon’s second wife, Rebecca Cline passed away on October 8, 1916, shortly after her 74th birthday. Amon and Beckie were living in Wray, Oklahoma, and had been married 10 years. On Rebecca’s headstone Amon wrote; “Second wife of Amon Cline… Gone but not forgotten. The love and comfort of his declining years.” Now only his children remained. Amon’s oldest child, Elizabeth (Cline) Smith died in January of 1917, she was 59.

For Europe, World War I began in 1914. At the outbreak of the War to End All Wars, the United States pursued a policy of non-intervention, avoiding conflict while trying to broker a peace. The United States eventually declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, and quickly began drafting young men for the war effort. Amon’s grandson, Carter C. Cline, was drafted and placed in the United States Army. Carter, born in April of 1893 was the oldest son of 43 year old Benjamin Cline, ‘Ben’ was the youngest of Amon’s offspring. American soldiers under General John “Black Jack” Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), arrived in large numbers on the Western Front in the summer of 1918. On June 30, 1918, 25 year old Army private, Carter Cline boarded the British troop-ship RMS Mauretania in New York, bound for action in World War I. Sailing through the U-boat infested Atlantic, the fast 31,938-ton vessel safely arrived Liverpool, England. Private Cline was joined to Company “A” 358th Infantry Division. The 358th’s first campaign was the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, fought September 12 to 15. This three-day attack was part of a plan by General Pershing in which he hoped Americans would break through the German lines and capture the fortified city of Metz, located in northeast France. It was the first large offensive launched mainly by the United States Army in World War I, and the attack caught the Germans in the process of retreating. The battle cost 7,000 in American casualties; 4,500 were killed, 2,500 wounded.

The 358th next offensive was far more involved; the Meuse–Argonne offensive began a short time later, on September 26, 1918. This epic battle was a major part of the final Allied offensive of the war, which stretched along the entire Western Front. It lasted 47, long days and was the largest in United States military history, involving 1.2 million American soldiers. The offensive was also the deadliest and bloodiest battle in the history of the United States Army, resulting in over 350,000 casualties, including 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives and an unknown number of French lives. American losses were worsened by the inexperience of many of the troops, the tactics used during the early phases of the operation and the widespread onset of the global influenza outbreak called the “Spanish flu”. A staggering 95,786 Americans were wounded; the Army captured 26,000 German’s as POWs. It was one of a series of Allied attacks, known as the Hundred Days Offensive, which fortunately brought the war to an abrupt end. The Meuse–Argonne offensive finally ended on November 11, 1918; the last day of World War I. Although Carter’s time in battle was far less than Amon’s Civil War duty, Carter was among the over 95,000 injured in combat and thus received the Purple Heart for his wounds. At the conclusion of World War I, Carter departed France aboard the cruiser, USS North Carolina (ACR-12) in late May of 1919, heading back to Oklahoma. Once home, 26 year old Carter married young, 19 year old Mrytle Stafford on Saturday, June 28, 1919.

On June 18, 1922, Benjamin Franklin Cline was found dead (in Oklahoma) from multiple gun shot wounds in his back. The 47 year old, was Carter Cline’s father and Amon’s son. The unknown assailant had used a .32 caliber pistol and was never found or identified.

In 1930, the elderly 96 year old Amon was living with his son James and his wife Emma. Sharing the Cline farm residence in Grady, Oklahoma was James’ 21 year old son Denver, married daughter Eva (Cline) and her husband Alton Williams. Rounding out the house hold of 7 family members was young 12 year old Garland Williams, son of Alton and Eva.

It wasn’t until 1953 when Amon’s last two surviving children died. James A., passed away on March 9, in Oklahoma, he was 89 years old. Then Susan (Cline) Wilson died in Pickens County Georgia, she was 82.

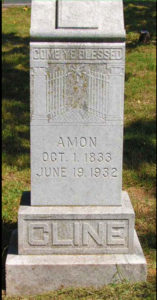

Above: Several Cline family members are laid to rest in the Terral, Oklahoma, Cemetery, located just outside the small agricultural town. The names include the following; Amon, and his wives Sarah Ann, and Rebecca J., Benjamin F. and his wife Dessie O., their young daughter Era, James A., and his wife Emmer Lou, Elizabeth (Cline) Smith and her husband Rufus Smith.

Amon Cline passed away quietly in Grady, Oklahoma, on June 19, 1932, he was 98 years old.

Above: Grave site of Amon Cline

Putting his life historically into perspective, Amon lived through some fascinating times in America. While he never traveled west of Oklahoma, Amon surely read of the famed old west gunfighters who came and went. He outlived countless such as; Billy the Kid (1859–1881), Jesse James (1847-1882), all four of the Earp brothers including Wyatt (1848–1929). The Younger brothers, Bat Masterson, Butch Cassidy and even the dreaded Clanton’s were all gone before Amon died. During his lifetime Amon saw the invention of the radio, telephone, and even the automobile.

– Rick Cline

I am very proud to say, Amon Cline is my great, great grandpa.

If you or someone you know is a descendant of Amon Cline, and there are hundreds of us, please inform them of this web page and encourage them to share this family information.

Other books by Rick Cline:

Note: This will be an on-going project, changes and up-dates will be made as they are discovered. Any and all discovered errors and or corrections, misspellings, photos etc., are welcomed.

Last page up-date, August 31, 2022